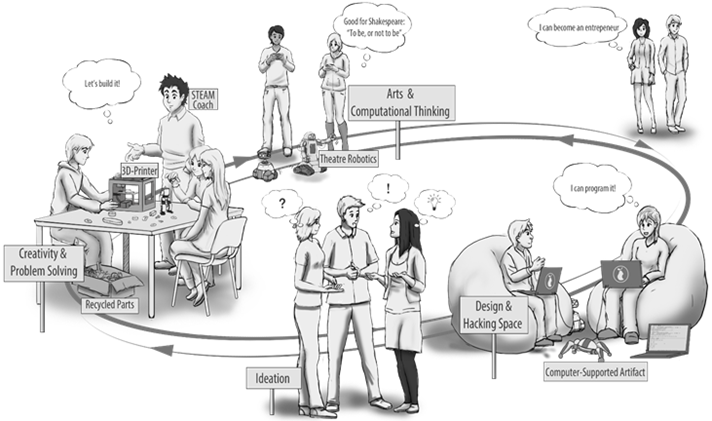

The eCraft2Learn ecosystem is built on the ideas of inquiry- and design thinking-based approaches. We shall utilise an inquiry-based approach, more specifically called project-based learning (PjBL). PjBL is based on inquiry and problem-solving processes in the subjects areas of science, technology, engineering and math. The eCraft2Learn project will actively pursue and foster the inclusion of the arts in the development and implementation of PjBL. In PjBL, the learning process is constructed around projects in which the students are working (see Blumenfield et al., 1991). Students have the freedom to choose the subject matter and to define the central content of the project they want to work with. Products like computer animations and websites can trigger communication and collaboration (see Blumenfield et al., 1991; David, 2008; Helle, Tynjälä, & Olkinuora, 2006; Tal, Krajcik, & Blumenfeld, 2006). Students develop their own questions, which are open-ended and which may lead to diverse solutions (Savery, 2006).

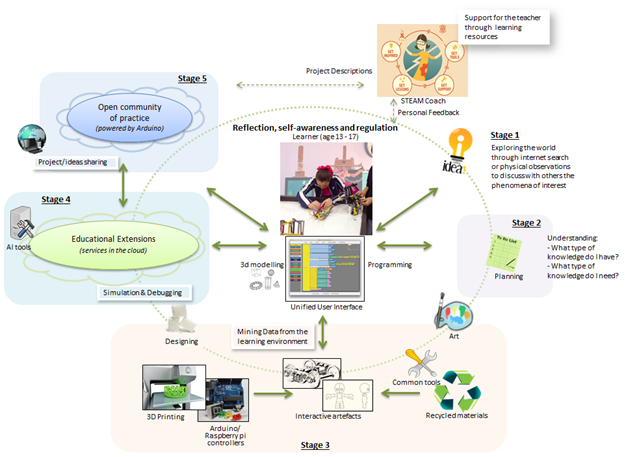

The eCraft2Learn pedagogical model enhances learner’s awareness of learning process and self-regulation (which includes self evaluation). It promotes learner’s personalised learning pathway by enhancing the design of technology implementation and designing the necessary support available (WP4). Pedagogical model also meets users’ needs and increase users’ engagement through participatory design approach. Model supports teacher’s role as a coach. The eCraft2Learn ecosystem is designed to support learners, teachers, peers and other stakeholders (e.g., facility managers) in making the crafts- and project-based learning a reality.

The eCraft2Learn ecosystem consists of two interlinked parts: a technical core and a pedagogical core. As explained above, the pedagogical core of the eCraft2Learn ecosystem in based on PjBL.

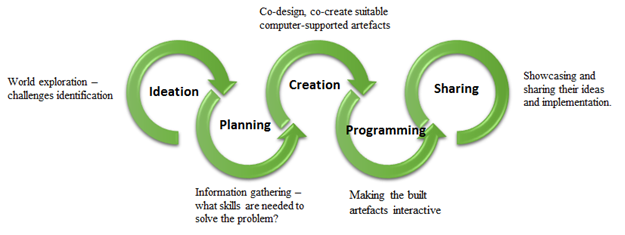

The pedagogical core consists of 5 interlinked stages: ideation, planning, creation, programming and sharing.

The technical core of the ecosystem, provides technical solutions to support the implementation and deployment of the pedagogical core (PjBL). As such the technical core includes: physical electronics (e.g., Arduino boards, Raspberry Pi, resistors, LEDs, sensors, 3D printers, etc.), and a unified user interface (digital platform) through which different digital tools can be accessed. Each of the five pedagogical stages is supported by the technical core as indicated below:

STEAM is used here as an educational approach to learning. In this approach, science, technology, engineering, arts and mathematics are seen as access points for guiding student activities, such as inquiry, dialogue and critical thinking, which enhance learning. This approach is assumed to produce students who take thoughtful risks, engage in experiential learning, persist in problem- solving, embrace collaboration and work through the creative process (see the following link: http://educationcloset. com/steam/what-is-steam/). Skills relating to the arts can be developed through product design. Introducing new digital technologies can encourage the incorporation of new materials and disciplines (see https://www.createeducation.com/blog/code-create- corelli-college/).

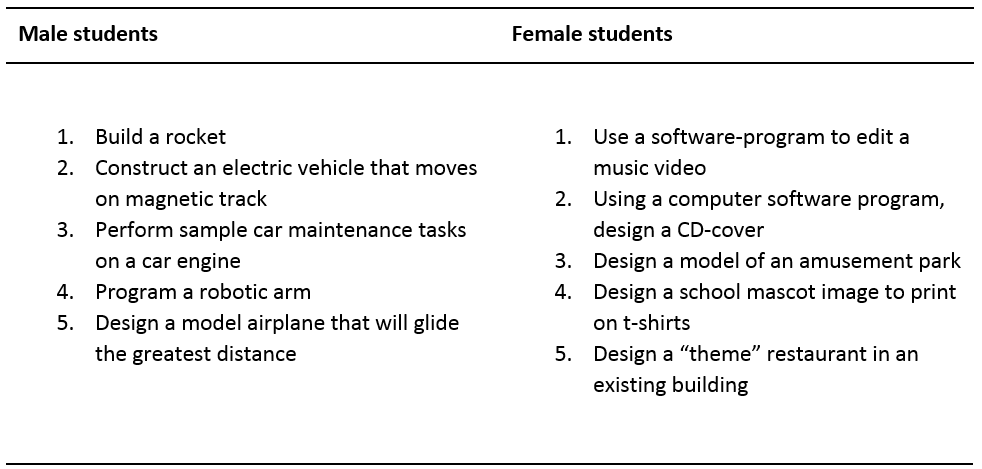

STEAM provides a way to engage boys and girls of all ages to explore the idea of electronics and technology (Magloire & Aly, 2013). The inclusion of arts and craft in science projects enables a space for creativity and innovation during the process. Electronics and technology usually attract more boys than girls, and girls have traditionally been more attached to artefacts when the product was meaningful to them (Magloire & Aly, 2013). According to Fristoe, Denner, MacLaurin, Mateas and Wardrip-Fruin (2011), girls’ interest in creating games is mainly in the context of relationships, social interactions and storytelling. Therefore, working in teams could fascinate girls because of the social interaction aspect (Mäkitalo-Siegl & Fischer, 2013) as well as arts and craft (Magloire & Aly, 2013) to work with projects involving electronics and technology. Weber and Guster (2005) have studied gender-based preferences towards technology. The population of their study consisted of middle school students and high school technology education classes. They found no differences in activity between genders; however, significant differences were found in relation to design and use. ‘Females found design activities more interesting when males preferred utilising types of activities’ (Weber & Guster, 2005, p. 59). Table 1 presents the top five activities among male and female students. ‘Since making is based on what is personally relevant to an individual, it allows people of all backgrounds to pursue their interests and to use technological tools to develop their own projects. It can create more channels for girls to positively identify with computer science and engineering fields’ (Intel Report, 2014 p. 7).

How to keep boys and girls motivated?

Table 1. Activities rated most interesting by male and female students at middle school and high school levels (Weber & Guster, 2005, p. 61)

Gender also has an influence on cooperation in groups. Previous research indicates that students’ positive academic performance is connected to single-gender conditions (see Harskamp et al., 2008; Light, Littleton, Bale, Joiner, & Messer, 2000). This has been explained in terms of similar working manner as well as attachment (Greenfield, 1997; Newman, 1998; Whitley, 1997). However, there is also evidence that gender conditions have no influence on the performance of groups, even though it was found that there were differences in terms of acting between mixed-gender and single-gender groups (Mäkitalo-Siegl & Fischer, 2013; Underwood, Underwood, & Wood, 2000). Male students are reported as being generally more interested in computers; therefore, it might be easier for them to work together on computer-supported tasks (Greenfield, 1997; Newman, 1998; Whitley, 1997).

The use of e-textiles to integrate arts and STEM education in computing education can broaden participation, especially among females (Peppler, 2013, p. 38). E-textiles are cloths or other textiles that include electronic components that are often woven in. The e-textile design includes creative coding, the artistic envisioning of material science and inventive electronics (see Peppler, 2013). There are several examples of how to modify clothes and shoes using electronic components on the internet. Using 3D-printing, micro processing technology and Arduino, students animate toys, clothing and artworks without working on screen-based programming and more academic work, which does not appeal to all students. In this way, we can capture the interest of students who would rather do and make things within the new computer sciences (see https://www.createeducation.com/blog/code-create-corelli-college/).

The cross-cutting idea of the eCraft2Learn pedagogical design is personalised learning, which is a progressively student-driven model. Zmuda, Curtis and Ullman (2015, p. 7) note that in ‘personalised learning, a student is deeply engaged in meaningful, authentic, and rigorous challenges to demonstrate desired outcomes’. Personalised learning also serves as a base for a project-based approach because of meaningful and authentic challenges. Moreover, the project-based approach includes different stages whereby the student is proceeding progressively. It is a student-driven model with more or less degrees of freedom, depending on the student’s prior knowledge and experience and the task and goals of the curriculum. We endeavour to connect the project to a realistic context – students’ everyday life – so that they can see the relevance of this project and the connection between school (school subjects) and the world outside of school (see also digital fabrication and making in education, Blikstein, 2013; Gershenfeld, 2007). Students explore the world in order to identify questions or puzzling situations, which might then turn out to be a problem for which they have to find a solution. The student plays a central role in project-based learning, which gives him/her an opportunity to engage in in-depth investigation of worthy topics. This approach gives the learner greater autonomy when constructing personally-meaningful artefacts, which are seen as the representations of their learning (Papert (1980),Grant, 2002, p. 1).

We do know that inquiry-based learning processes and working in teams can be challenging for students (Kollar, Fischer, & Slotta, 2007; Linn, 2006). In particular, when students are mostly working in teams, they face several challenges, which might occur due to lack of engagement on knowledge-construction processes regarding formulating questions, challenges, collecting evidence, interpreting results, explaining and evaluating these explanations and the process or different processes of project work (Mäkitalo-Siegl, Kohnle, & Fischer, 2011). Therefore, support should be offered in order to help students with the inquiry-based and design-thinking processes as well as with working in teams. This kind of support might require expert guidance or scaffolding as well as small group scripting. However, an open question is whether those students who are facing challenges are using the help that is available from multiple sources (e.g. teachers, peer learners, experts, the online environment; see Mäkitalo-Siegl & Fischer, 2011; Huet et al., 2013).

Blikstein, P. (2013). Digital Fabrication and ’Making’ in Education: The Democratization of Invention. In J. Walter-Herrmann & C. Büching (Eds.), FabLabs: Of Machines, Makers and Inventors (pp 1-22). Bielefeld: Transcript Publishers.

Blumenfield, P. C., Soloway, E., Marx, R. W., Krajcik, J. S., Guzdial, M., & Palincsar, A. (1991). Motivating Project-Based Learning: Sustaining the Doing, Supporting the Learning. Educational Psychologist, 26, 369-398.

David, J. L. (2008). Project-Based Learning. Educational Leadership, 65, 80-82.

Fristoe, T., Denner, J., MacLaurin, M., Mateas, M., & Wardrip-Fruin, N. (2011). Say it with systems: expanding Kodu's expressive power through gender-inclusive mechanics. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Foundations of Digital Games (pp. 227-234). ACM.

Gershenfeld, N. (2007). Fab: The Coming Revolution on Your Desktop--from Personal Computers to Personal Fabrication. New York: Basic Books (AZ).

Grant, M. M. (2002). Getting a Grip on Project-Based Learning: Theory, Cases and Recommendations. Meridian: A Middle School Computer Technologies Journal, 5(1). http://www.ncsu.edu/meridian/win2002/514/3.html retrieved on 2.3 2017.

Greenfield, T. A. (1997). Gender- and Grade-Level Differences in Science Interest and Participation. Science Education, 81(3), 259-275.

Harskamp, E., Ding, N., & Suhre, C. (2008). Group Composition and Its Effect on Female and Male Problem-Solving in Science Education. Education Research, 50(4), 307-318.

Helle, L., Tynjälä, P., & Olkinuora, E. (2006). Project Based-Learning in Secondary Education: Theory, Practice and Rubber Sling Slots. Higher Education, 51, 287-314.

Huet, N., Dupeyrat, C., & Escribe, C. (2013). Help-Seeking Intentions and Actual Help-Seeking Behavior in Interactive Learning Environments. In S. A. Karabenick, & M. Puustinen (Eds.), Advances in Help-Seeking Research and Applications. The Role of Emerging Technologies (pp. 121-146). Charlotte, NC: IAP-Information Age Publishing.

Intel Report (2014). MakeHers: Engaging Girls and Women in Technology through Making, Creating, and Inventing. Online at http://www.intel.com/content/dam/www/public/us/en/documents/reports/makers-report-girls-women.pdf retrieved on 15.3.2017

Kollar, I., Fischer, F., & Slotta, J. D. (2007). Internal and External Scripts in Computer-Supported Collaborative Inquiry Learning. Learning and Instruction, 17(6), 708-721.

Light, P., Littleton, K., Bale, S., Joiner, R., & Messer, D. (2000). Gender and Social Comparison Effects in Computer-Based Problem Solving. Learning and Instruction, 10(6), 483-496.

Magloire, K. & Aly, N. (2013). SciTech Kids Electronic Arts: Using STEAM To Engage Children All Ages and Gender. 3rd Integrated STEM Education Conference. http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/stamp/stamp.jsp?arnumber=6525220 retrieved 2.3.2017.

Mäkitalo-Siegl, K., & Fischer, F. (2013). Help Seeking in Computer-Supported Collaborative Science Learning Environments. In S. A. Karabenick & M. Puustinen (Eds.), Advances in Help-Seeking Research and Applications: The Role of Emerging Technologies (pp. 99-120). Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing.

Mäkitalo-Siegl, K., Kohnle, C., & Fischer, F. (2011). Computer-Supported Collaborative Inquiry Learning and Classroom Scripts: Effects on Help-Seeking Processes and Learning Outcomes. Learning and Instruction, 21(2), 257-266.

Newman, R. S. (1998). Adaptive Help Seeking: A Strategy of Self-Regulated Learning. In D. H. Schunk & B. J. Zimmerman (Eds.), Self-Regulation of Learning and Performance: Issues and Educational Applications (pp. 283-301). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Papert, S. (1980). Mindstorms: Children, computers, and powerful ideas. Basic Books, Inc.

Peppler, K. (2013). STEAM-Powered Computing Education: Using E-Textiles to Integrate the Arts and STEM. Published by the IEEE Computer Society. http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/stamp/stamp.jsp?arnumber=6562697 retrieved on 15.2.2017.

Savery, J. R. (2006). Overview of Problem-Based Learning: Definitions and Distinctions. The Interdisciplinary Journal of Problem-Based Learning, 1, 9-20.

Tal, T., Krajcik, J. S., & Blumenfeld, P. C. (2006). Urban Schools´ Teachers Enacting Project-Based Science. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 43, 722-745.

Underwood, J., Underwood, G., & Wood, D. (2000). When Does Gender Matter? Interactions during Computer-Based Problem Solving. Learning and Instruction, 10(5), 447-462.

Weber, K. & Custer, R. (2005). Gender-Based Preferences toward Technology Education Context, Activities, and Instructional Methods. Journal of Technology Education 16(2) 55-71.

Whitley, B. E. Jr. (1997). Gender Differences in Computer-Related Attitudes and Behaviour: A Meta-Analysis. Computers in Human Behavior, 13(1), 1-22.

Zmuda, A., Curtis, G., & Ullman, D. (2015). Learning Personalized. The Evolution of the Contemporary Classroom. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

![]()

![]() eCraft2Learn H2020-731345 - UEF.

eCraft2Learn H2020-731345 - UEF.

This work is licensed under a License Creative Commons Atribution 4.0 International.

This project has received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 Coordination & Research and Innovation Action Under Grant Agreement No 731345.